Filtering History: Photojournalists’ Access to U.S. Presidents, 1977-2009

Volume 34, No. 3

By Erin K. Coyle & Nicole Smith Dahmen

For decades, political leaders have released their own photographs and controlled opportunities for photojournalists to record them, either by staging events (called photo ops) or by restricting access. These restrictions, however, often serve as a deterrent to photojournalists who work to provide accurate and realistic images and a true visual historical record. When presidential access is limited or restricted, the historical record is also limited to images that have been filtered and recorded by the White House staff and often designed to promote a political agenda and a positive image of the presidency.

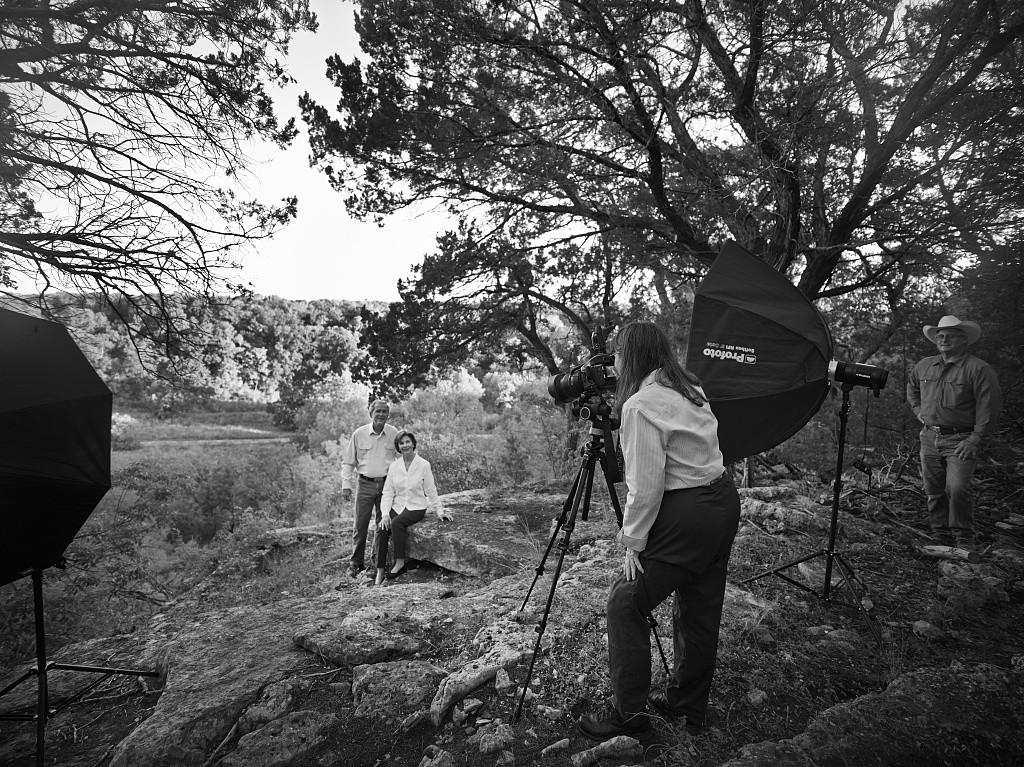

Source: Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. The scene at photographer Carol M. Highsmith’s photo shoot of former president George W. Bush and former first lady Laura Bush at their 1,600-acre Crawford Ranch near Crawford in McLennon County, Texas. An aide to the president looks on. Crawford McLennon County, Texas. 2014. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2015630529/. (Accessed September 07, 2017.)

This study examined photojournalists’ perceptions about the influence of such White House practices to control photographic images after the Vietnam War and Watergate. The authors interviewed nine photojournalists who covered the White House from 1977 to 2009. In addition to the interviews, the authors also researched photojournalists’ books, a leading professional organization’s journal, letters sent to the White House by leaders in professional organizations, news articles, and the National Press Photographers Association Code of Ethics. These additional documents helped to determine whether photojournalists’ stories and themes were unique to interviewed photojournalists or were shared by a collective community of photojournalists required.

The research revealed that concerns about access were subtly different during the two phases addressed in this study. Moreover, common themes emerged from the interviews. For instance, photojournalists frequently noted their devotion to providing the public with independently recorded images. Photojournalists also indicated they did not expect to have access to highly sensitive or personal events, but they recalled that restriction grew over time. This increasingly restricted access, the photographers noted, limited whether and how photojournalists could photograph presidents. Believing that photographs shape how people recall historical events involving the president, some photojournalists warned that image management practices, at times, had shaped ways in which people could perceive the president and some historical events.

This study reveals that interviewing communication professionals is a valuable method for learning about journalism history — a method that could be used by undergraduate or graduate students interested in learning more about communication history from primary sources. Exercises may help students learn how to perform their own interviews and think more about the role photographs play in shaping collective memories. Students may start by reading and discussing the article. Then students may complete exercises to practice performing interviews, learn more about roles that photojournalists play in helping to record history, and think about how photographs may influence our understanding of history.

General Questions for Discussion:

- What roles are described for photojournalists in the article?

- How would you describe at least two common themes regarding photojournalists’ perceptions of their access to photograph the president?

- What do examples from the article indicate about how access to a president relates to a photojournalist’s ability to contribute to the historical record of the presidency?

- How has access to presidents changed over the period covered in the article?

- How did stories recounted in oral history interviews contribute to your understanding of whether, when, where, and how photojournalists have been able to take pictures of presidents?

Exercise 1

Students can learn context by watching a four-minute video, “Photojournalism and the American Presidency:”

https://www.cah.utexas.edu/photojournalism/about.php

Before they watch the video, ask students to think about roles that photojournalists perceive for images of the American presidency. After they watch the video, ask students to discuss what the video and the article indicate about roles for photographs in the historical record. They could address the following sample questions:

- What have photojournalists indicated that photographs of presidents show people about each president?

- What have photojournalists indicated about how photographs help audiences perceive moments in history?

- What have photojournalists suggested that photographs contribute to people’s understanding of the president and history?

Exercise 2

Photojournalists have said that access to each president is crucial for photojournalists to be able to provide independently recorded images of each president. Students may learn about one award-winning photojournalist’s experience photographing presidents by watching a one-minute video, “Access: Inside the Bubble:”

https://www.cah.utexas.edu/photojournalism/transcript.php?media_id=7

Before they watch the video, ask students to consider what the video indicates about photojournalists’ access to the president. Students may learn more about that photojournalist’s experience photographing the president by watching a second one-minute video, “Looking into the Souls of Presidents:”

https://www.cah.utexas.edu/photojournalism/transcript.php?media_id=5

After the students have watched both videos, assign students to work in groups of two. Assign each student to ask the other student questions, listen carefully to the other student’s answers, and take careful notes. After they interview each other, discuss what students learned and what they found challenging from interviewing each other. When interviewing, they may use the following sample questions:

- What did Dirck Halstead’s description of access to presidents indicate about photojournalists’ access to presidents?

- How would you compare his brief description of photojournalists’ access to presidents to the article’s description of photojournalists’ access to presidents?

- Why does access to the president matter for photojournalists?

- What did Dirck Halstead’s description of photojournalists’ roles and the article’s description of photojournalists’ roles teach you about photojournalists’ perceptions of their roles as recorders of history?

Exercise 3

Students may practice interviewing a faculty member or a family member who they would feel comfortable asking about roles images served in shaping memories of historic events or figures. They should use this opportunity to practice asking questions, listening carefully to responses, and taking careful notes on the responses. They may use this opportunity to learn more about whether and how photographs have helped influence memories of people or events. Students may ask the following sample questions:

- Do you recall a photograph, which was taken at least 10 years ago, that influenced your perception of the president?

- What did the photograph show?

- What did you think of the president before you saw that photograph?

- What did you think of the president after you saw that photograph?

- How do you think that photograph influenced your memory of the president or the event shown in the picture?

Suggested Resources

American Folklife Center. “Oral History Interviews.” Accessed on June 23, 2017. http://www.loc.gov/folklife/familyfolklife/oralhistory.html#tips.

Baylor Institute for Oral History. “Introduction to Oral History Manual.” Accessed on June 23. 2017. http://www.baylor.edu/oralhistory/index.php?id=931751.

Paul Lester. On Floods and Photo Ops: How Herbert Hoover and George W. Bush Exploited Catastrophes. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2010.

Library of Congress. “Oral History and Social History.” Accessed on June 23, 2017. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/lessons/using-history/procedure.html.

Minnesota Historical Society Oral History Office. “Putting Together an Oral History Project: Overall Guidelines.” Accessed on June 23. http://www.mnhs.org/collections/oralhistory/ohguidelines.pdf.

Judith Moyer. “Step-by-Step Guide to Oral History.” Accessed on June 23. http://www.oralhistory.org/web-guides-to-doing-oral-history/.

Oral History Association. “Principles for Oral History and Best Practices of Oral History.” Accessed on June 23. http://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices/.

Donald A. Ritchie. Doing Oral History. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995.

Samuel Proctor. “Tutorials: Beginning an Oral History Project.” Accessed on June 23. https://oral.history.ufl.edu/research/tutorials/.

Southern Oral History Program at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “A Practical Guide to Oral History.” Accessed on June 23. http://sohp.org/files/2013/11/A-Practical-Guide-to-Oral-History_march2014.pdf.

Southern Oral History Program at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “10 Tips for Interviewers.” Accessed on June 23. http://sohp.org/files/2012/04/10-Interview-tips.pdf.

Southern Oral History Program at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “An Oral History Bibliography.” Accessed on June 23. http://sohp.org/files/2012/04/Oral-History-Bibliography-2011.pdf.

University of Texas at Austin. Reading America’s Photos. Accessed June 30, 2017. https://www.cah.utexas.edu/photojournalism/photojournalists.php.

Barbie Zelizer. Covering the Body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.