EDITORS NOTE: This post contains teaching materials to be used with an article by James Kates published in Volume 30, Issue 1, 2013, of American Journalism: “A Path Made of Words: The Journalistic Construction of the Appalachian Trail,” pages 112-134. The article is available, for free, at the Taylor & Francis website.

A Path Made of Words: The Journalistic Construction of the Appalachian Trail

By James Kates

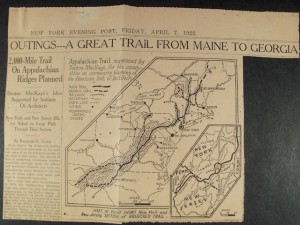

In “A Path Made of Words,” James Kates tells a particular kind of story about the creation of the Applachian Trail, focusing on how natural landscapes can be crafted and “sold” to the public based on scenic, cultural and historical value, recreational opportunities, and many other factors. His article examines the building of the Appalachian Trail (1921-1937), which remains America’s most famous outdoor-recreation project. In just 16 years, the rationale behind the trail shifted markedly as writers sought to define its meaning and usefulness.

The classroom materials below are meant to stimulate discussion of Professor Kates’ article and to suggest some avenues for similar research. The materials can be adapted for use by anyone from advanced high-school students to graduate students. Professor Kates welcomes comments and questions at katesj@uww.edu.

Into the Archives

Historians work with two broad categories of source materials: “primary” and “secondary.”

Primary sources are materials created at the time history is made. They include letters, diaries, documents, scrapbooks, census materials, drawings or photographs, artifacts and the like. Historians examine these materials to get a close, original look at a place, person, phenomenon or period under study.

Secondary sources are created after the fact. They include books and articles in historical journals, or perhaps historical television programs, films, Web sites or museum displays. Historians examine these materials to gain background for their work. They also use them to see how other historians have interpreted historic happenings. Once a historian learns how others have interpreted history, he or she might look for a new “angle” or interpretation of a story. Some stories have lots of angles. For example, scholars estimate that about 15,000 books have been written about Abraham Lincoln.

Secondary sources usually are found in libraries. Even small public libraries and school libraries have secondary sources on history. The largest collections of these sources are found in university libraries.

Primary sources usually are housed in archives. An archive may be run by a university, or by a historical society or other nonprofit group. Local, state, provincial and national governments have archives. Sometimes archives are kept by the organizations whose history they document. Business organizations, for example, often maintain their own archives about their corporate history.

Primary sources are collected, edited, catalogued and preserved by archivists, who make them available to scholars for research. Archivists receive materials from individuals, families, and organizations. Often these collections are referred to as “papers.” To give an example, a prominent author might donate his papers (or sell them) to a university. These might include correspondence with friends, family, fans, critics and publishers, early drafts of published works, unpublished manuscripts and other materials of interest.

Once a collection of papers is received, archivists go through it to organize the contents in a way that will be accessible to researchers. Correspondence (copies of incoming and outgoing letters) might be organized by time period, by the person being written to, or by subject. Sometimes archivists will assemble separate subject files dealing with particular topics. Once the papers are organized, they are put in acid-free boxes for storage on archive shelves. Some collections are small (one or two boxes); others may be huge (hundreds of boxes). In the past, popular collections were microfilmed; today they may be digitized and made available online. Many times, however, the only way to see a collection is go to the archive and request the actual items. It is a special thrill to hold a letter signed by a U.S. president, or a poem scratched in pen by a prominent writer.

Archivists compile finding aids that help researchers locate the materials they are seeking in a particular collection. A finding aid will usually include a summary of the subject matter, along with a box-by-box list of the collection’s contents. Many archives make their finding aids available online. This is particularly helpful for a researcher who may be visiting an archive for a short period of time, or for someone who is seeking specific materials in a large collection.

Here is the online finding aid for the papers of the MacKaye family. This collection includes most of the primary sources used in James Kates’ article about the Appalachian Trail. It is housed at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College: http://ead.dartmouth.edu/html/ml5_fullguide.html

Note that this is an enormous collection (361 boxes) covering many members of the family, so access to a finding aid in this case is especially important!

Many archives also provide online catalogues for researchers wondering what collections the archives might have. Here is the archives catalogue (called “ArCat”) for the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison: http://arcat.library.wisc.edu

The society’s archives are particularly strong in the area of mass-communication history. For example, the society has the papers of Rod Serling, the television writer best known for “The Twilight Zone.” If you enter his name in ArCat, you’ll see information about his papers, including a link to a finding aid.

Exercise One: Seeking a Topic

Visit a nearby archive or make a “virtual visit” via the Web. Using the archive’s catalogue, find a collection of papers that interests you. Use the finding aid to locate a specific box or boxes within the collection that may hold materials of interest. Outline a topic that would be suited to a research paper of about 10 pages. If you’re dealing with a large collection or a prominent person, you’ll probably have to narrow your topic to one aspect or incident. A paper on Rod Serling, for example, could deal with his authorship of the 1956 TV drama “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” or the problems he had with TV network censors in the early 1960s.

Crafting the Message

A key point in Professor Kates’ article is that journalists promote natural landscapes in myriad ways as times change. For example, a forest that once was touted primarily as a source of timber might later be “sold” to the public as a haven for recreation.

Benton MacKaye conceived of the Appalachian Trail as an experiment in social engineering. He thought the trail would be lined with residential camps in which citizens would devise new modes of living. This never happened. But the trail itself thrived as a weekend haven for middle-class recreation-seekers. MacKaye re-crafted his message over time and helped found the wilderness movement. The Appalachian Trail has always been “A Path Made of Words”: Writers have helped shape the public’s view of its usefulness over time, even as the trail itself has stayed much the same.

Exercise Two: “Selling” the Trail

For this exercise, divide the class into teams of a few students apiece. Each team will envision itself as the “promotional committee” for the Appalachian Trail during a given time period. The team will produce a public-service message of about 100 words to be read on the radio or reproduced in print. The goal is to “sell” the AT to the public based on the predominant concerns and public-policy themes of each decade.

Each category below includes one publicly accessible source that will introduce students to the themes of a given time frame. Groups should read more on the Internet or in print sources to help craft a message that will be true to their time period.

The 1940s: National defense and World War II

Army physical training manual, 1946 (note the Army’s expansive definition of “fitness,” which includes not just strength but alertness, mental agility and leadership skill): http://www.cgsc.edu/carl/docrepository/FM21_20_1946.pdf

The 1950s: The fear of juvenile delinquency

Short film, “What About Juvenile Delinquency?”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoqnuC8P8wc

The mid-1950s to early 1960s: The Cold War and the threat of communism

Efforts by Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy to emphasize youth fitness: http://www.jfklibrary.org/JFK/JFK-in-History/Physical-Fitness.aspx

1960s: The battle for wilderness preservation

Wilderness Act of 1964: http://www.wilderness.net/NWPS/documents//publiclaws/PDF/16_USC_1131-1136.pdf

1970s: Earth Day and the environmental movement

Wisconsin Historical Society site on Senator Gaylord Nelson and the founding of Earth Day: http://www.nelsonearthday.net

Present day (version 1): Climate change and environmental concerns

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Earth Day site: http://www.epa.gov/earthday

Present day (version 2): The “obesity epidemic” and concerns about inactivity among American youth

First lady Michelle Obama’s youth fitness campaign: http://www.letsmove.gov

Other Environmental Journalists and Authors

Many journalists and authors have attempted to shape popular and scientific views of environmental issues through their writings. Here are a noteworthy few, any one of whom would make a good subject for a term paper:

George Perkins Marsh (1801-1882) has been called the first American conservationist. His book “Man and Nature” (1864) warned that deforestation could turn woodlands into “deserts.”

John Muir (1838-1914) was a nature writer whose books and magazine articles enthralled millions. Muir wrote vividly of the beauty and rapture of wild places, and he led campaigns for wilderness preservation as founder of the Sierra Club.

Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946) was the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service under President Theodore Roosevelt. Pinchot established the doctrine of “wise use” under which forests were groomed for sustainable benefits such as timber and flood control. He was a strong advocate of “publicity,” believing that press coverage was his best weapon in the battle for conservation.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) worked as a game manager and forester, but ranged much further afield intellectually to become of the pioneers of environmental ethics. A prolific and gifted author, he wrote widely for both scientific and popular audiences. His book “A Sand County Almanac” (1949), published shortly after his death, would become a bible of the modern environmental movement.

Robert Marshall (1901-1939) was a forester and plant scientist who helped found the Wilderness Society in 1935. Independently wealthy from an inheritance, he dedicated his fortune and all his energies to promoting wilderness preservation through his writings.

Rachel Carson (1907-1964) was a marine biologist who worked for the U.S. government before becoming a bestselling nature writer. Her last book, “Silent Spring” (1962), sounded an alarm over the effects of chemical pesticides and herbicides on human and animal life.

Howard Zahniser (1906-1964) was the longtime editor of “The Living Wilderness,” the magazine of the Wilderness Society, and author of the 1964 Wilderness Act, which preserved millions of U.S. acres. Zahniser drafted the legislation in 1956 and spent eight years lobbying for its passage. He died just four months before President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill into law.

Annie Dillard (b. 1945) is an American writer whose 1974 book “Pilgrim at Tinker Creek” won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction. The book melds spirituality and meditation with close observation of the wonders of nature near her then-home in Roanoke, Virginia.

Bill McKibben (b. 1960) is an environmental writer, speaker and activist whose works warn of the dangers of global warming. Articulate and outspoken, he provokes considerable debate among environmentalists themselves, for example with his campaign urging colleges and universities to divest themselves of investments in any companies that produce fossil fuels.

The National Trails System

As Professor Kates’ article notes, the Appalachian Trail was built largely with volunteer labor, but government assistance was vital to the project. As decades passed, it became clear that government sponsorship was necessary to promote major trails and to protect them from incursion. The National Trails System Act of 1968 designated the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail, then under construction, as the first “National Scenic Trails.” Another category, “National Historic Trails,” was created in 1978 to recognize trails that had special historical significance. The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, for example, follows the route of the 1804-1806 Lewis and Clark expedition from near St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon. It is not a hiking trail, but rather a route linking historical sites with recreation opportunities along the way. Historic trails depicting difficult chapters in history (such as the forced removal of American Indians from ancestral lands) can spark conflict over differing interpretations of the American story.

Some of the national trails are still being built. The North Country National Scenic Trail, the longest of the scenic trails authorized by Congress, covers about 4,600 miles from upstate New York on a winding route that ends in North Dakota. Only about half the trail is completed. It is administered by the National Park Service, but built and maintained mostly by volunteers in the North Country Trail Association. In a plan that Benton MacKaye would appreciate, the NCTA has 28 chapters, each of which is responsible for building and maintaining a section of the trail.

National Trails System: http://www.nps.gov/nts

North Country Tail Association: http://northcountrytrail.org

Take a look at a trail near you. How was it built (or how is it still being built), not just in terms of its physical structure, but in terms of its larger meaning? Is it a place of spiritual solace, a home for recreationists, or a link to history and culture? If the trail has existed for more than a few years, how has its meaning changed? Has it been “sold” to the public in different ways during different decades?

Other Links

Appalachian Trail Conservancy: http://www.appalachiantrail.org

New York-New Jersey Trail Conference: http://www.nynjtc.org

American Society for Environmental History: http://aseh.net

Forest History Society: http://www.foresthistory.org