By Carrie Teresa, Niagara University

Teaching the Article: Ideas and Exercises

This set of exercises is designed to introduce students to the black press, a collection of newspapers produced by and for the black community beginning in the early nineteenth century. Through these exercises, students will be encouraged to think critically about the symbolic value of achievement in sport over time and the importance of celebrities as representations of cultural values and achievements. They will receive practice in historical methods by excavating black press content from the past, paying special attention to the textual and visual elements of these newspapers in order to assess how cultural meanings and values are shaped and reflected in news production. Finally, they will consider the nature of historical narratives themselves – who is remembered, why are they remembered, and how are they remembered over time.

Primary resources

Many black press newspapers have been digitized and are available via ProQuest and America’s Historical Newspapers databases. America’s Historical Newspapers has many local, small-market newspapers that had short lives, while ProQuest features the major metropolitan titles in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and others. Google has also digitized and made available the Baltimore Afro-American, which still publishes today. Black press scholar Kim Gallon has begun an online resource for inquiry into the black press, the Black Press Research Collective, which highlights recent developments in black press historiography and archival availability. The BPRC is an excellent source for students and instructors hoping to become familiar with black press newspapers.

Students are also encouraged to reach out to their institution’s research librarian, who may be able to direct them to institutional, city-, or state-related special collections. In these collections, such as the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University, students will have the opportunity to interact with physical – rather than digital – copies of primary source newspapers.

Suggested primary resources

Atlanta Daily World

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: December 1931

Baltimore Afro-American

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: January 1895

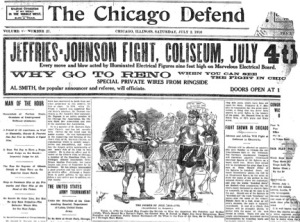

Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition)

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: July 1909

Cleveland Gazette

Source: America’s Historical Newspapers: African American Newspapers, 1827-1998 [digital]

Earliest date available: January 1895

Kansas City/Topeka Plaindealer

Source: America’s Historical Newspapers: African American Newspapers, 1827-1998 [digital]

Earliest date available: January 1889

New York Amsterdam News

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: November 1922

Philadelphia Tribune

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: January 1912

Pittsburgh Courier

Source: ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Historical Newspapers [digital]

Earliest date available: March 1911

Savannah Tribune

Source: America’s Historical Newspapers: African American Newspapers, 1827-1998 [digital]

Earliest date available: January 1889

Exercise 1: Meaning-making in black press coverage

Exercise 1A: Introduction to the black press – textual analysis

The study of journalism is an important component in understanding the commonly shared cultural beliefs and values of a group of people at a particular historical moment. News stories as significant as Johnson’s 1910 victory over Jim Jeffries operate as, to quote Michael Schudson, “a reservoir of stored cultural meanings.” In this exercise, students will examine via digital archives two or three months’ worth of local black press content. They will perform a textual analysis of the content, which is a close reading of the rhetorical cues and narrative elements of the news stories to uncover the cultural meanings embedded within them.

Questions

- What do you notice about the layout of the newspaper? Pay special attention to mastheads, headlines, pictures, and illustrations.

- What subjects do black press journalists take on?

- What news stories make the front page?

- What sections are included in the newspaper?

- Do these stories match conceptions of what constituted then-contemporary notions of “newsworthiness”?

- What advertisements do you see?

- What can you discern about the readership of these newspapers given the content?

Exercise 1B: Introduction to the black press – visual analysis

Coverage of Johnson’s victory was supplemented by photographs, which often dominated the front pages of these newspapers. The visual representation of Johnson is telling – he is depicted either as a fearsome warrior or a well-dressed gentleman. As visual communication scholars have noted, photographs often augment textual meaning in news; as Andrew Mendelson noted, “cultural ways of seeing obstruct the constructed nature of photographs, making certain meanings appear to be the only way to interpret a photograph.” Often people paid to have their photos published in black press newspapers; having one’s photograph published in a black press newspaper often signaled high social status. In this exercise, students will assess how visuals like this one suggest meanings that augment the texts that they accompany.

Questions

- Who is visually depicted on the front pages of these newspapers?

- What do the visuals suggest about the person?

- Are there any clues about who may have paid for the privilege of having their photograph published in the newspaper?

Secondary sources

Black press historiography

- Jinx Coleman Broussard and John Maxwell Hamilton, “Covering a Two-Front War: Three African-American Correspondents During World War II,” American Journalism 22, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 33-54.

- Andrew Buni, Robert L. Vann of the Pittsburgh Courier: Politics and Black Journalism (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1974.

- Brian Carroll, “This Is IT!” Journalism History 37, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 151-162.

- Hayward Farrar, The Baltimore Afro-American, 1892-1950 (Westport: Greenwood, 1998).

- Kim Gallon, “‘How Much Can You Read About Interracial Love and Sex without Getting Sore?’: Readers’ Debate over Interracial

Relationships in the Baltimore Afro-American,” Journalism History 39, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 104-114.

Relationships in the Baltimore Afro-American,” Journalism History 39, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 104-114. - Roi Ottley, The Lonely Warrior: The Life and Times of Robert S. Abbott (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1955).

- Armistead S. Pride and Clint C. Wilson II A History of the Black Press (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1997).

- Patrick Washburn, The African-American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2006).

- Clint C. Wilson II, Black Journalists in Paradox: Historical Perspectives and Current Dilemmas (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991).

Meaning-making in news

- Daniel A. Berkowitz, ed., Cultural Meanings of News (Los Angeles: Sage, 2011).

- Elizabeth Bird, and Robert W. Dardenne, “Rethinking News and Myth as Storytelling” in The Handbook of Journalism Studies, ed. Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch (New York: Routledge, 2009), 205-217.

- Carolyn Kitch, “Mourning ‘Men Joined in Peril and Purpose’: Working Class Heroism in News Repair of the Sago Miners’ Story,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 24, no. 2 (2007): 115-131.

- Andrew Mendelson, “The Construction of Photographic Meaning,” in Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy Through the Communicative and Visual Arts James Flood, Shirley Brice Heath, and Diane Lapp (New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 2:27-36.

- Michael Schudson, The Sociology of News, 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2011).

Exercise 2: Comparison of celebrity coverage in black press and mainstream press

African American athletes, actors, and musicians were increasingly gaining “celebrity status” in the early twentieth century as newspapers increasingly paid attention to entertainment-centered news stories. In the mainstream press, African American celebrities often faced the same snubs and prejudices as ordinary black citizens. In the black press, however, these celebrities received great attention. This exercise will give students a sense of how mainstream journalism reflected the prejudices of Jim Crowism and how the black press attempted to combat prejudice reflected in mainstream news narratives.

Questions

- How does coverage of these figures differ between the black press and the mainstream press? Differences can include: tone of reporting, visual representations, and quantity and placement of coverage.

- What surprised you about the coverage in each type of newspaper?

Secondary Sources

- Daniel J. Boorstin, “From Hero to Celebrity: The Human Pseudo-event” in The Celebrity Culture Reader, P. David Marshall (New York: Routledge, 2006), 72-90.

- Richard Dyer, “Stars as Images,” in The Celebrity Culture Reader, P. David Marshall (New York: Routledge, 2006), 153-176.

- Joshua Gamson, Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

- David Marshall, “Intimately Intertwined in the Most Public Way,” in The Celebrity Culture Reader, ed. P. David Marshall (New York: Routledge, 2006), 315-323.

Exercise 3: Assessing the symbolic value of achievement in sport

Johnson became popular fodder for black press newspapers that often connected his status as a celebrity with the black community’s fight for civil rights. Scholars have noted the importance of achievement in sport in the fight for civil rights – the idea that equality in sport would lead to equality in public and civic life generally. It is clear that, at least at first, Johnson’s victory over Jeffries held great symbolic value to the black press journalists covering the fight.

This exercise explores other instances whereby athletic achievement in sport had an impact on black Americans’ struggle for freedom. Appropriate athletes for this exercise might include: Jesse Owens, Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali, Ernie Banks, Michael Jordan, and Venus and Serena Williams, to name only a few.

Questions

- Does athletic achievement in sport still hold symbolic value for the black community? How about for other historically marginalized groups?

- What role do journalists play in framing the achievements (and failures and controversies) of athletes of color? (This question also lends itself to a comparison of mainstream and black-centered news publications.)

Secondary sources – African American participation in sport

- Arthur R. Ashe Jr., A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African American Athlete, 1619-1918 (New York: Warner Books, 1988).

- William C. Rhoden, Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete (New York: Broadway Books, 2007).

- David K. Wiggins and Patrick B. Miller, Sport and the Color Line: Black Athletes and Race Relations in Twentieth Century America (New York: Routledge, 2004).

- David K. Wiggins and Patrick B. Miller, The Unlevel Playing Field: A Documentary History of the African American Experience in Sport (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

Exercise 4: Finding the forgotten greats

The figures mentioned in Exercise 2 are some of the most iconic black celebrities of the early twentieth century by virtue of the fact that they – one way or another – garnered the attention of the mainstream press. However, there is a cadre of talented and celebrated artists and athletes who, by virtue of never garnering mainstream attention, have been forgotten by historians.

In this exercise, students will again visit two or three months’ worth of early twentieth century black press content to find those forgotten greats.

Questions

- What celebrities were considered most newsworthy this period? Make a list of the top five actors, musicians, athletes, and performers featured during that period.

- Have you heard of any of the celebrities on this list? Which ones? Do a quick Google search of each name – who has had the most biographies and articles written about him/her?

- Are there any celebrities you haven’t heard of or for whom you cannot find any information? Why do you think these figures have been “forgotten” in contemporary times?

Exercise 5: Assessing Johnson’s complex mediated memory

Johnson has emerged in popular culture in a variety of ways over time. In the contemporary context of continuing tension between race and equality under the law, his story continues to resonate with members of the African American community. For memory studies scholars, the past is used to cultivate contemporary aims and agendas. The strength of the past lays not in the forgone events themselves, but rather in how those events are remembered and applied to contemporary context. According to Barry Schwartz, memory serves as both a model of the present and a model for the present by both “reflecting on the past as well as acting as a frame for understanding the present.” For example, like Muhammad Ali in the 1960s, controversial 1990s heavyweight champion Mike Tyson has begun to use Johnson’s memory as a tool with which to frame his own legacy through his autobiography, Undisputed Truth, and its accompanying HBO special, as well as his short-lived documentary television series, Being: Mike Tyson.

Looking at Johnson‘s “memory texts,” this exercise will encourage students to contemplate Johnson’s complex role as a civil rights icon. Texts appropriate for this analysis might include the following:

- The Great White Hope (film, 1970)

- Ken Burns’s Unforgivable Blackness (documentary, 2005) (The PBS website for this film also includes valuable resources for instructors interested in lesson plans about Johnson.)

- Trevor Von Eeden’s The Original Johnson: Volumes 1 and 2 (graphic novel series, 2009-2011)

- Mike Tyson’s Undisputed Truth series (2013-2014)

Questions

- When is Johnson’s memory evoked? What is the historical context of production for this memory narrative?

- What parts of Johnson’s story are remembered, forgotten, or emphasized in this memory narrative?

- How has Johnson’s story changed over time?

Secondary sources – Memory studies

- Jill A. Edy, “Journalistic Uses of Collective Memory,” Journal of Communication 49, no. 2 (Spring 1999): 71-85.

- Barry Schwartz, “Frame Images: Towards a Semiotics of Collective Memory,” Semiotica 121, no. 1/2 (1988): 1-40.

- Barbie Zelizer, “Reading the Past Against the Grain: The Shape of Memory Studies,” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 12, no. 2 (June 1995): 211-239.

- Eviatar Zerubavel, “Social Memories: Steps to a Sociology of the Past,” Qualitative Sociology 19, no. 3 (1996): 283-299.