The article is freely available at the Taylor & Francis website.

Breaking Bread, Not Bones: Printers’ Festivals and Professionalism

in Antebellum America

Award Winner, Best American Journalism Article 2013

Volume 30, Issue 3, 2013

By Frank E. Fee

Americans in the early decades of the nineteenth century confronted change at every turn. Everything about life in the new nation was up for negotiation as new political and social patterns inherent in the ideas of American democracy combined with new technologies and the nascent Industrial Revolution. This new dispensation called for new economic and business models and spawned movements that advanced new ideas in education, social welfare, and equality and lifted living standards, including literacy.

American printers were no different in facing change and choices. Rising literacy created demand for a variety of print products – newspapers, magazines, pamphlets and tracts – just as new production technologies and advances in distribution methods made it possible to reach larger audiences. The artisanal print shop with the traditional master-journeyman-apprentice structure gave way to so-called “professional” editors whose intellect and communication skills were more prized than their ability to set type. Elsewhere in the printing establishments, just as they were in other crafts, specialization and differentiation of tasks and work roles were hallmarks of the new age.

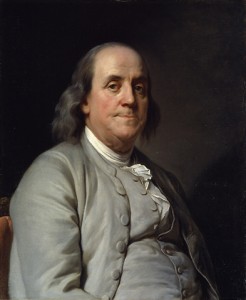

Competing for ideas, not to mention financial support, printers of this early era often indulged in scabrous discourse through their columns that yielded bruised feelings and, occasionally, battered bodies. They longed for the public esteem and financial comforts they saw enjoyed by doctors, lawyers, and the clergy, but struggled with how to attain them. In a sense, these men – and a very few women – were struggling to define who they were and their place in the new society. In “Breaking Bread, Not Bones: Printers’ Festivals and Professionalism in Antebellum America,” Frank Fee examines how editors and publishers confronted the challenges of change and helped define journalism in the new nation. The article argues that social occasions – festive dinners marking the birth date of iconic printer-statesman Benjamin Franklin – provided a means of drawing often warring editors and publishers together to affirm journalism’s importance to the democracy and the ideals to which they adhered or at least aspired. In time, the social capital these dinners reaped would help bring about formal organizations to advance the industry.