Volume 35, No. 1, 2018

Winter Issue

A. J. Bauer is the author of “Journalism History and Conservative Erasure.” In an interview with Editorial Assistant Virginia Harrison, he discussed the longstanding yet overlooked tradition of journalistic criticism in the U.S., journalists’ duty to challenge social hierarchies, and conservative journalistic criticism’s relationship to fake news.

1. Why do you think the U.S. lacks a tradition of journalistic criticism?

It doesn’t. In 1974, prominent journalism historian James Carey wrote an essay claiming “that a tradition of press criticism does not exist in the United States.” As a historian of conservative media activism, who has spent the better part of a decade compiling archival materials that evidence conservative press criticism dating back to the late 1930s, I find Carey’s claim both confounding and problematic. The trouble stems from Carey’s normative definition of “critique,” which he distinguishes from “attack.” Carey desired the “emergence of a critical community” inclusive of both the press and the public it seeks to represent. He envisioned proper press criticism as a feedback loop between journalists and readers, where critique serves to bring these two parties together around a consensual news judgment, rooted in a shared conception of reality. According to Carey, critiques that enunciate or reinforce the gap between professional news judgment and the reality experienced by readers, without abiding by certain “terms and manners,” ought not be considered as ‘criticism.’ In “Journalism History and Conservative Erasure,” I demonstrate that Carey’s idealized conception of press criticism is too narrow and relegates a rich and consequential tradition of conservative media criticism outside journalism historians’ frame of vision.

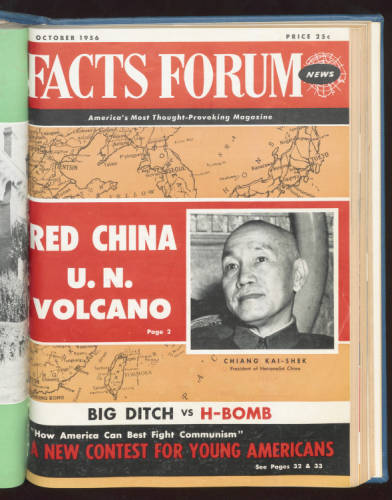

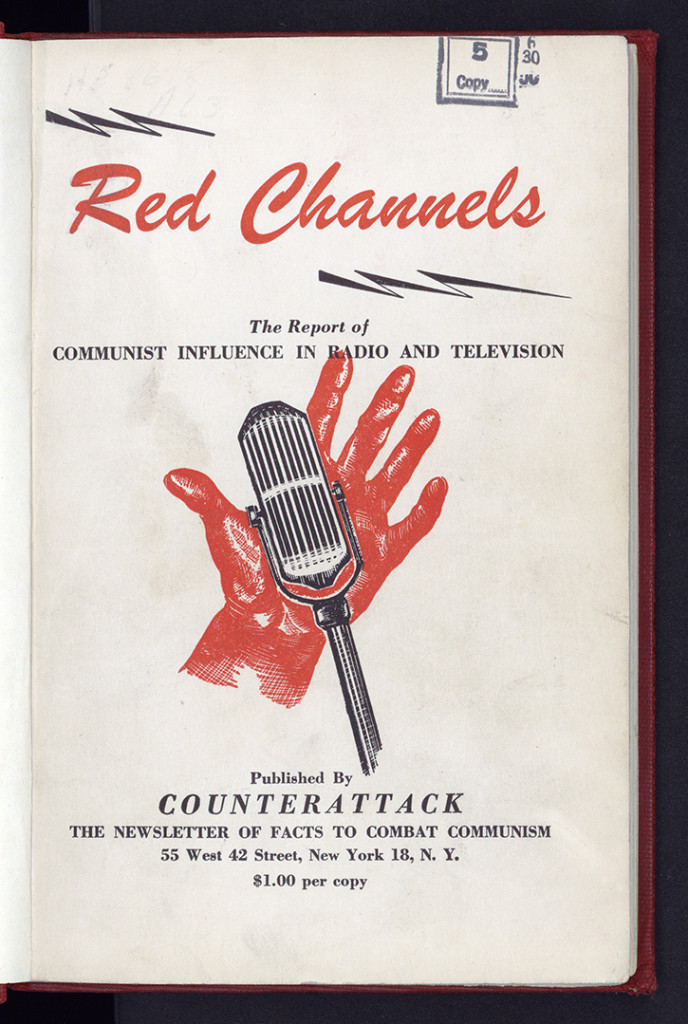

2. Many right-wing critiques of the 1950s-60s media sound very similar to the critiques of the press today. Should journalists be concerned that they are facing similar critiques as they did 50 years ago?

I don’t think journalists should be concerned, but I do think they should consider the structural reasons why critique is inevitable in this country. While nominally a liberal democracy, the United States has several chronic conditions that prohibit the sort of idealized public sphere that might serve as a consensual basis for such journalistic professional values as fairness, neutrality, and objectivity. The continuing legacies of white male supremacy and capitalism, to name just two primary sources of the many hierarchies in the United States, have long imbued every aspect of life. These intersecting social and cultural hierarchies, and the complicated political identities they foster, yield myriad unequal and conflicting social positions from which individuals assess the meaning of the news of the day. From its outset, the modern conservative movement has been especially adept at organizing around the foil of the mainstream press. As such, the gap between the reality depicted by journalists as “news,” and the reality understood by the conservative grassroots, has remained stubbornly persistent.

3. How should the profession address these recurring complaints?

Professional journalists ought to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. It’s okay if doing so results in criticism from members of the public who either benefit directly from traditional social hierarchies or who otherwise share some political or cultural affinity with those who do. We should stop considering political disagreement in terms of “complaints.” Professional journalists ought not be in the customer service business, and just because a portion of the public disagrees with a reporter’s news judgment, or refuses to accept the reality produced through the procedures of professional journalistic reporting, does not mean that journalists need to accommodate them or meet them in the middle. There are now plenty of right-wing news outlets to service those consumers. While the professional press is indeed a contested site in the ongoing crisis of objectivity in the United States, it is ultimately the responsibility of progressive journalists and activists to engage with conservative media criticism and to compellingly counter its narratives.

4. What is the value of journalistic criticism in a free press society? Should we be concerned we often dismiss journalistic criticism as right-wing motivated rather than taking it seriously?

The value of journalistic criticism lies in the expression of the social and cultural pluralism that becomes obfuscated by any attempt to convey a perfectly consensual “objective” reality. I think it is more than proper for journalists, scholars, and progressive activists to confront and criticize right-wing media criticism. But as historians, if we are to understand the drives and subjectivities that shape our politics, we must take pains to consider the effects of such criticism, historically, on conservative journalists, activists, and their supporters. Taking conservatism seriously does not mean embracing an apolitical or morally relative stance toward it. Taking conservatism seriously means spending at least as much time understanding as we do passing judgment.

5. The fear in the 1950s that people could not interpret propaganda sounds a lot like today’s fear about people not being able to detect fake news. How is fake news a form of journalistic criticism?

The claim “fake news” is not in itself journalistic criticism, but is instead an indication of the presence of a critical disposition that needs to be better historically understood. What causes conservatives to distrust mainstream news reporting, to read it critically and skeptically, to withhold benefit of the doubt, to treat innocent errors as evidence of malice? How has that critical disposition been developed over time, consistently since the 1950s and even earlier? These are the sorts of questions I am suggesting journalism historians ought to be asking.

6. Can you recommend additional sources on journalistic criticism in the U.S. for people who want to learn more?

Folks interested in contemporary journalistic criticism can look to progressive outfits like Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting and Media Matters for America, or right-wing outfits like Accuracy in Media and Media Research Center.